Mary Shelley (and a bit of Steve Jobs)—On the Art of Creative Waiting

incubating an epic dream in a Swiss villa-gone-wild

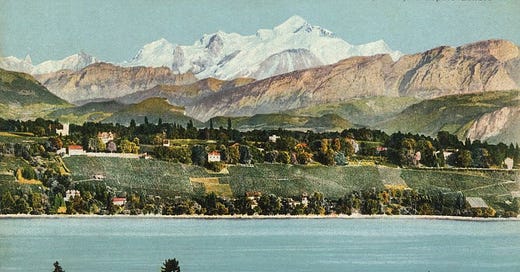

Mary Shelley had no idea what to write. The year was 1816, and the vibes had gone apocalyptic. She and a crew of writerly powerhouses had gathered at Lake Geneva for a summer holiday, though their summer would be anything but normal. The year before, an Indonesian volcano had blasted ash into the stratosphere, dimming the sun across the Northern Hemisphere, leading to a slow-motion cascade of crop failures, riots and starvation from Jakarta to Kansas that had only begun to snowball. One million people would perish over the next few years from these knock-on effects, making it the most deadly volcanic eruption ever, but the troupe of writers on vacay didn’t know that yet. As they twiddled their pens and peered out the window, it just rained and rained.

The gang was eclectic: Lord Byron, age 28, a formidable poet who’d fled his spiral of debts and scandals back in London, and Dr Polidori, 21, Bryon’s personal medical doctor, had rented a palatial villa with primo Lake Geneva views. Byron was such a gossip topic that Polidori had landed a publishing contract to keep a diary of their travels (just imagine your 21-year-old GP being paid to write about your holidays together). They were joined by Mary, 18, then a young mother and thus far unpublished; her infant child; her step-sister Claire Clairmont, 18; and her lover and future husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, 23, a dashing poet, intellectual, and political activist.

Byron and Polidori’s pad, Villa Diodati, became party central. With the crew cooped up for days due to rain, entertainment options ran low and intrigues thickened. Polidori became obsessed with Mary but she fought him off; Claire was into Byron but he wasn’t having it (though she was already preggers with his kid, her 1st his 3rd)—and god knows what else went down. Perpetually cold, lacking the internet, in the evenings the little troupe crowded around a blazing fire and amused themselves with books of vintage German ghost stories.

“We will each write a ghost story,” pronounced Lord Byron, shepherding their entertainment/tension nexus to the next level with this supernatural challenge (Claire was exempt). The two published heavyweights got to work straightaway: Byron wrote a spooky vignette, a fragment of which appears at the end of his poem Mazeppa, and Shelley cooked up the poetic A Fragment of a Ghost Story. Polidori hit a home run, hatching the idea that would become his novel The Vampyre, now credited as the first modern vampire novel.

Mary, on the other hand, was stuck.

“I thought and pondered—vainly,” she wrote. “I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.”

Her authorial anxiety ratcheting up by the day, Mary got high on science via second-hand fumes. Lightning crackled over the dark lake as Byron and Percy stayed up late night after night. They discussed the findings of Erasmus Darwin, John Abernathy and others, musing as to how these ideas might relate to “the nature of the principle of life.” Luigi Galvani—who’d famously discovered that zapping a dead frog leg with electricity made it twitch—got a bunch of air time. While the bros discoursed, Mary simply listened, and in retrospect, seems to have grasped the implications of this potent brew on a deeper level than the speakers.

One night, after silently absorbing yet another witching-hour chat, her unconscious delivered. “When I placed my head on my pillow,” she wrote, “I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arrived in my mind.” And in this extraordinary “waking dream,” as she later called it, the key scenes and impressions that would become her first novel, Frankenstein, unfolded in an epic burst. She saw a “pale student of unhallowed arts” standing over pieces of corpses he’d stitched into a ghastly, giant collage of a man. And via the workings of a powerful engine, he brought this dead matter to life and consciousness.

The rest is history. More than two hundred years after this singular dream event, Frankenstein is still widely-read, still inspiring new adaptations, and with each fresh turn of the technological screw (like our current AGI doom-soup) still astonishingly prescient.

I’ve found myself mulling on the mystery of Mary’s creative process. How on earth did she incubate such a monster concept, still echoing after centuries?

Much has been made of her references, her parents, unique upbringing and influences. Google Scholar alone returns over 59,900 citations for Frankenstein. Heck, astronomers have even tracked down the suspected date of her waking dream by coordinating reports of the weather and moon that summer. But there’s an aspect of her process that I haven’t seen mentioned, and that deserves to be singled out as one of the conditions that made her dream possible—her creative waiting.

Mary could have easily jumped on the first idea that came to mind. “Churn out a shitty first draft,” is the advice many a 21st century writer would give. Like, how about a thinly-veiled ghost-version of Polidori haunting a teen mom with a raging case of writer’s block, just to get the pen flowing. Hmm, plenty of fresh material there, one can imagine her thinking. But she did not succumb to lesser inclinations.

She set a bold intention—“a story to rival those which had excited us to the task,” as she put it—and seems to have never even considered half-baked sketches. Each morning, no matter how mortified she felt, Mary stuck with her intention, and when the trio of significantly older literati dudes asked if she had a story yet, she said no.

Such presence of mind at the tender age of 18 (or any age really) is nuts, especially given her situation. The villa must have been a tension swamp, what with the unfolding volcano horror, the variety of sexual intrigues, the striking age differences, the intense, 19th century gender gap, plus the party’s personal baggage and whatever other entanglements. If only the internet was a thing, it would have been tempting to bleed off the anxiety, and swoon into an infinite doomscroll.

Instead, Frankenstein’s villa-gone-wild origin story mirrors the nature of electricity itself. An electric charge is formed via positive and negative poles, and that’s exactly what Mary set up. She held a big positive intention, and with each mortifying acknowledgement that she hadn’t yet reached it—with each solid no—she generated more creative charge. Then more, and more as she waited, until it had fully galvanized the cauldron of her unconscious, and unleashed her sensational waking dream.

This is no easy task. A comfortable nervous system would rather not bother. It’s hard to build that kind of charge for yourself, to create your own poles and hold that tension—let alone stew around in it—not knowing what the outcome will be.

In our culture, waiting has a bad rap. After all, if you’re waiting, what’s to show off on Insta? Maybe it’s not the hottest look, but creative waiting has always been a maverick superpower. In 1998, a professor asked Steve Jobs what his next strategic move at Apple would be, given that Apple seemed to be hopelessly stuck at a tiny fraction of the PC market share. Jobs merely smiled and replied, “I am going to wait for the next big thing.” He proceeded to do exactly that, leading to the innovation of the iPod, and then the iPhone. Throughout his career, Jobs made spectacular moves by waiting, again and again, to spot and catch his next big wave.

Creative waiting is a receptive state, but it’s not a passive, couch-potato deal. Mary fed her mind; Steve scanned the horizon. Both were intensely focused, fully charged, yet made ample room for serendipity. And both turned down anything less than their vision.

There’s also another, peculiar facet to creative waiting—a gut-level knowing. “Waiting is not mere empty hoping,” says the I Ching. “It has the inner certainty of reaching the goal. Such certainty alone gives that light which leads to success.” For some lucky folks this certainty might be quite specific. More often it seems to be directional: In the darkness of waiting, you somehow know that an idea or opportunity will come, even when it’s not at all apparent what such a new thing might be.

While Jobs’ certainty was legendary, we have only hints of Mary’s—the cool glint in the clarity of her reflections, the resolve in her successive no’s, the seriousness and laser-focused intent she applied to a minor, entertaining challenge. She wasn’t betting on a bad hand. However mortified she felt, some part of her knew what she was truly capable of.

We’re often pressed into waiting by events outside our control. It can be a switch to practice it consciously, to make it part of our own creative process. Give the things you’d rather forget a rummage and pluck out the scariest—the supernatural challenge, the seemingly-impossible biz objective that you know is actually tailored to your weirdo strengths. Somewhere in every vision, goal or aim meant for you there is a spark of certainty, and if you fan it, that flame will grow to light your path. And it’s ok to say no. It’s ok to boldly not have an idea yet. It’s ok to wait, and it’s definitely ok to de-wheel from the hamsterism of today’s productivity theatre. In fact, you might need to if you really want to dream up a monster story.

This was a great read - really captured the vibe of that Swiss lake house and the intellectual hothouse it must have been. Whew - to be a fly on the wall during some of those conversations! And my goodness, at 18, I could barely figure out how to rent an apartment for myself or structure a college book report. What a crew.

Loved this read, you really brought the ver creative waiting concept to life through the Mary Shelley & Lake Geneva example. It’s inspired me for my own creative journey. Plus I’m a sucker for anything involving the Romantics or the Victorians, takes me back to being a keen and green English literature undergrad!