How I Discovered Interstate 280 Was Inhabited

a few things you might not know about the World's Most Beautiful Freeway

In 2007, I was invited to make an artwork for an exhibition in San Francisco. I wanted to make a sculpture that responded in some way to the city, but I didn’t know much about SF. The situation presented a meta-problem: How do you uncover interesting information that you don’t know? I find this to be an ongoing issue when making art, so I’m always on the lookout for strategies that can expose me to interesting unknowns. Then, in the research phase of a project, I do them. And that is how I accidentally discovered that Interstate 280 was inhabited.

As a starting point for my project, I wanted to see the region. A good way to learn about a landscape is to simply take public transportation everywhere you can. Unlike driving, on public transport you’re free to focus on the environment. So, I took BART and Caltrain for the full extent of all available lines, and looked out the window.

On a Caltrain jaunt, I noticed an intriguing spot while heading toward downtown. As I-280 heads into the Financial District, Caltrain runs underneath the elevated freeway and parallel to a forest of giant concrete columns that support I-280. At one particular location, the columns were heavily painted with graffiti, and the space between them was open but unpaved, just sandy dirt and scrub grass. It was hard to see much detail as we whizzed past, so I went back to investigate on foot.

What I discovered was a weird world, an anti-microcosm of San Francisco.

Artists were flowing through this strange underpass zone. The freeway columns were extensively graffitied and constantly being reworked. Language had built up in dense layers like a physical chat thread. From the tags, it was clear that artists from far afield were visiting. For them, it was a premium spot, because the columns were easy to clandestinely access, relatively protected, and, like pricey billboards, had an absurdly high volume of eyeball traffic via Caltrain commuters. The attention economy had been hacked.

As I explored deeper, I encountered the inhabitation.

Deep within the site, there were openings in the bottom of the freeway. As I-280 coasted into downtown, soaring about 30 feet in the air, the smooth concrete was punctuated by several square holes. These inky, uncovered gaps had clearly been converted into residences.

Access was obviously a challenge, but also a defensive feature—this person or group had rigged a retractable ladder system. Over the next few months, I returned to the site about 7-8 times, and encountered the ladder in both up and down positions. I never glimpsed the inhabitant(s).

At another residence, personal items were visible alongside a fresco. Like the graffiti artists, these individuals were communicating with an unseen audience.

That year, we were approaching the apex of the real estate bubble. I consulted with an experienced Bay Area realtor who estimated that a 500 sq ft studio apartment in this neighborhood during 2007 would have rented for about $1200 per month. Now, it would go for $2500 per month. That’s 500 square feet.

If you’re seeking accommodation in the Bay today, from Google street view it is a simple matter to observe that across the Embarcadero section of I-280, the freeway has similar interior access spaces at every major connecting joint, though these spaces are typically secured with steel plate covers. To investigate this architectural phenomenon a bit more deeply, I called up CalTrans, and by luck spoke with a member of staff who’d worked on a retrofit of I-280. He remarked that because of freeway’s hollow, box-girder construction, these access voids allow for inspection and maintenance. The inhabitation has been a serious, long-term issue, he said, and a very dangerous one. In cold weather fires are started inside the freeway.

Just down the road, a dedication sign in Daly City identifies I-280 as the “World’s Most Beautiful Freeway,” so dubbed for its scenic views of the Santa Cruz Mountains and glimpses of San Francisco Bay. Even if you’ve never been to the region, you may have seen I-280: Up until 2021, the freeway’s badge was prominently featured in the official app icon for Apple Maps (below) and shipped with all just about all macOS and iOS products, apparently beloved because it passes through Cupertino, where Apple is headquartered. Check your nearest phone or laptop, who knows, you might still have it.

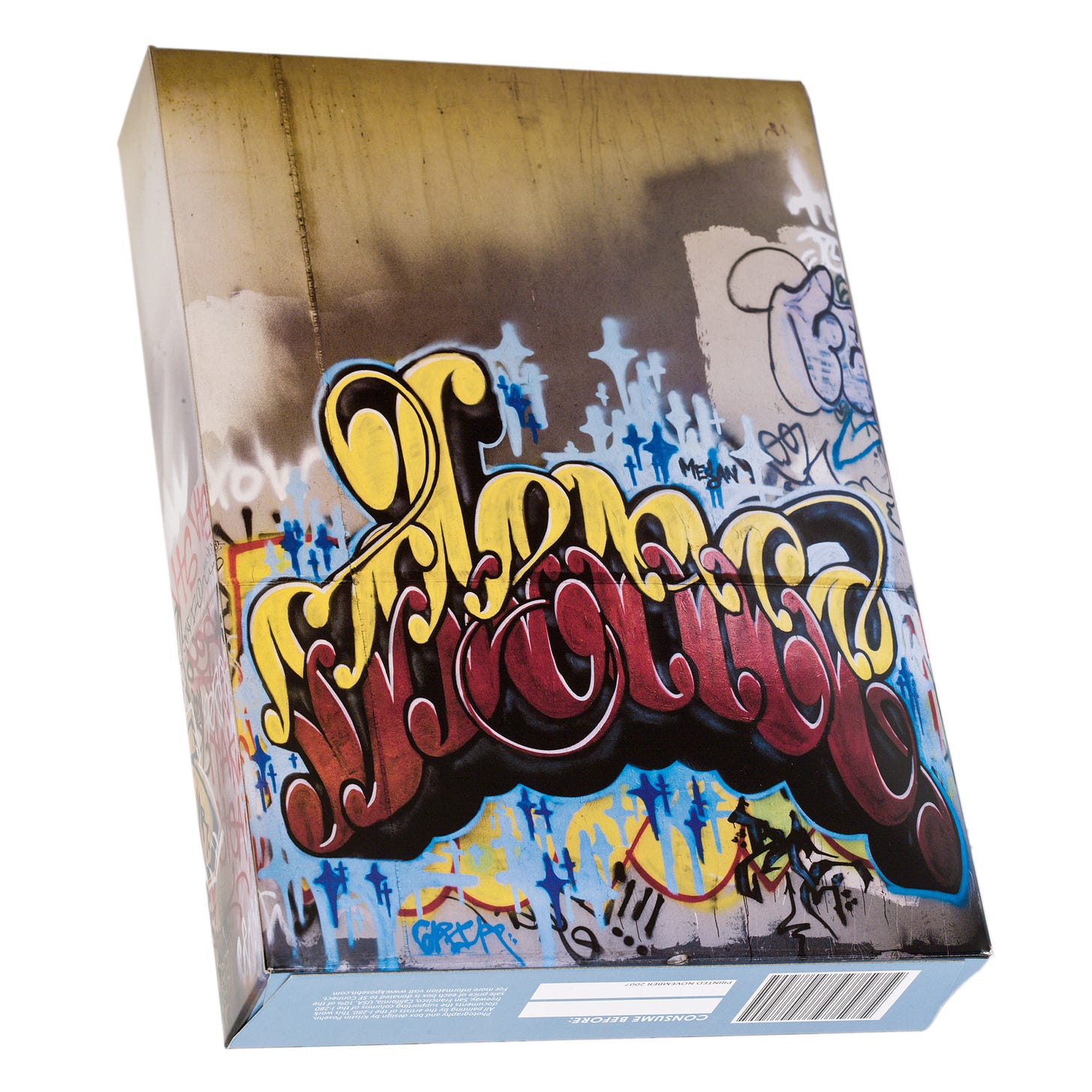

In the end, I made a sculpture based on this site titled Marshmallow Cosmos. To create the artwork, I documented supporting columns from this stretch of I-280, and reproduced them as a breakfast cereal.*

Here’s how I did it: Over the course of my visits, I made high-resolution photographs of the columns. I used a digital SLR camera with a ball head and tripod, and made arrays of photographs which were then stitched together with software to form intensely-detailed meta-images. Because the columns are curved, the images had to be unwarped to fit a rectilinear framework. Then, I reverse-engineered my favorite cereal box package, and designed a new one with freeway column images.

It’s always fun to approach a staid commercial supplier with a weirdo art fabrication idea. In this case, eyebrows were raised by the commercial packaging printer I called up, but they took the job (and maybe even enjoyed it). After printing, the boxes were packed and stored flat—I still hand-assemble, sign, and number them in small batches in my studio. I glue each box together, and seal a generic bag of breakfast cereal inside. You never know what kind you’ll get.

To my surprise, this work has given me a peek into the evolution of cereal box packaging over the last decade-plus—or rather, the devolution. Because I assemble in small batches, I’m an occasional full-shopping-cart-buyer of generic cereals, and a discerning customer. The size of Marshmallow Cosmos was fixed when it was printed, but cereal box dimensions across brands of all stripes have persistently shrunk, while the volume and weight of their contents has similarly withered. Every year we get a little less, and usually pay a little more. The relentless shrinkflation has been just as eye-opening to witness as the doubling of neighborhood apartment rental prices.

Sometimes people assume this artwork is about graffiti. It’s not. Marshmallow Cosmos is about a city and an anti-city. It’s about language and attention, how communities do and don’t speak to each other, strategies of commodification and subversion, advertising and contemporary art. It’s about things that happen right before the World’s Most Beautiful Freeway slides into the Financial District and downtown San Francisco. It’s about real estate, infrastructure, intimate moments in a kitchen, and secrets hidden in plain sight.

*One year later, in 2008, Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk bootstrapped their newly-formed Bay Area startup, Airbnb, with an election-themed breakfast cereal. Perhaps there was something in the air.