I sat down at a little orange-painted table in a parking lot behind a coffee shop. In Los Angeles we celebrate this area as a charming, semi-public space, but objectively it’s more like a huddle of metal furniture perched on cracked asphalt, bounded by weeds and a dumpster. Due to a pothole my coffee tilted right, dribbling onto my productivity calendar. I cracked open a thrifted copy of Stephen King’s Rose Red and lightly sniffed the first page. Above it all hung the the foamy blue sky, celestial and 72 degrees, which is how LA launders its squalor.

At a table just a couple feet away, a late-twenties woman with a strip of pink hair and a fellow with a shaggy beard chatted about therapists. They spoke at such a high volume that I couldn’t not overhear. Which I enjoyed, because it felt like myself and the screenwriter with frizzy blond hair working on his laptop at the other table were part of the convo.

Pink hair gal brought up a friend who’d been in the military and retrained as a therapist. “He’s an absolute moron,” she said, “he knows all these therapeutic techniques and doesn’t practice them.” Then she gave us a brief update on the progress of her own therapy, and how her therapist now suggests that she become a therapist, which she considered except the lifestyle isn’t a fit. And she confided that the biggest topic in her therapy lately has been the dawning insight that she has an intense tendency to judge herself. She was and still is mindblown, she emphasized, to discover that she suffers from such a horrifically judgmental inner critic.

“Excuse me,” I said, “I couldn’t help but hear you mentioning that you’ve discovered an inner critic. Does it have a flavor?”

“I’ve never thought of it like that,” she said, wrinkling her nose. She plucked a stray hair off her sleeveless black onesie, reflecting. “It’s kind of acidic.”

“That’s fascinating,” I replied. “It reminds me of an ex. He was an extraordinary miniature cow photographer, probably top three in the world. Soft, glowing light, complex maneuvers with the camera to make the cow look extra tiny. Natural, never posed. It went viral everywhere. But he could never really take in the success. After dinner one night he did a selfie with fans, and as we walked to the car he reeled off everything wrong with that day’s shoot. That’s when it hit me, the harshness and severity of his inner monologue. Gosh it sounds like you’re hard on yourself, I said to him. Well, how else could I have achieved all of this, he snorted, gesturing to his car and the restaurant as if the world was his pasture. He self-hated the rest of the car ride home. But he cleverly justified, even encouraged his self-hate as a process of optimization. Pretty soon after that, he started trying to optimize me. I haven’t thought about him in years. Hearing you today brought the pain of it all back.”

“No way,” she said. “I can’t believe how much effort it takes to even be able to see this stuff.”

“What do you think?” I asked the guy. He perked up at my engagement, exposing an 8.5x11” sheet of paper taped to the front of his t-shirt. It read ATTENTION in bold red type over a selfie of a woman crying, with a QR code to download her latest single.

“I grew up in rural Canada and started ice sailing before I could walk,” he said. “It’s true, you can use that critical voice to beat yourself into getting better on the ice. But at what cost? It’s not just a bunch of thoughts. Over time it breaks down your body. There’s wear and tear, chronic stress, energy drain. Hearing that story, it sounds like your ex Stockholm Syndrome’d himself. It’s a setup that makes you the victim…” he paused, gazing at the palm trees beyond McDonalds, before continuing, “…of yourself. And it cuts you off from your power.”

“He was 5’2”,” I added, nodding along as I picked off another chunk of my gluten-free donut. “I wonder if he saw miniature cows in a way that taller people couldn’t.”

“What I’m so f***** sick of,” said the girl, clenching her chipped red nails around air, “is exerting all this effort to think positive thoughts about myself. I keep imagining a different outcome. But nothing changes.”

“Have you ever seen a finger trap?” I asked. “It’s a long, thin cylinder, barely larger in diameter than your finger, made of woven paper, fiber, or plastic. You put a finger into each end, and then, as you attempt to pull your fingers out, the weave tightens around you. The harder you pull, the tighter it gets. You can only escape the trap by relaxing. I think about that a lot. I’m both sides of every problem I’ve ever had. Because in our everyday lives, the weave, to a large extent, is linguistic. Even the time I peed my tutu in kindergarten. That was awful, but there’s a political prisoner in Yemen right now who’d trade anything for that freedom. It’s not a problem to them. I created my problems. And I can un-create them too.”

“How?” she said, staring at me with a prune face of confusion and disbelief, her pale shoulders curling inward like half moons.

“Good question,” I replied. “I don’t know. Like you, I had that voice super bad. I tried everything to get rid of it—forest pilates, a kidnapping retreat, you name it. The turning point finally happened in a session with a grotesquely overpriced performance psychologist. She led me through a series of peculiar psycho-exercises in a New York City office that occupied an entire floor. I sat in different chairs, acting out each part in a teary-angry dialogue with my inner critic. As I hopped between chairs, I wondered how she got away with such an obscene hourly rate for something I could have learned on Wikipedia. It finally came to a head when she said to me, in all seriousness, Now befriend your inner critic. At first that struck me as the stupidest thing I’d ever heard. Then I got strangely clear. I realized she’d just asked me to do something impossible. For years, I’d been defining this thing in my experience as a critic and simultaneously trying to get rid of it. But only a critic would decide to get rid of a critic, so that was clearly insane. Yet it was equally ludicrous to expect an entity defined as my critic to be friendly. The whole push-pull could never really be resolved. It was all so absurd. I finally got it. I’m a critic. I’m critical. And I need the cut of criticality. Imagine always trying to eat your food completely whole, without ever slicing an onion or carving a chicken breast. We cut, bite, and chew at least three times a day, and that’s not all. Our stomachs make acid so we can break down food still further, otherwise we’d never be able to absorb the nutrients we need to live. Ideas and images, thoughts and feelings need to be decomposed and broken down too, that’s what great artists do. Instead of trying to rid myself of criticality—which, of course, is an intensely critical urge—I can wield it, the way that sushi chef in Shinjuku does a knife.”

Buzzing like an elephant wasp, we heard the drone before we saw it. A windowless dark grey blob the size of a Mini Cooper drifted over the flower shop, flying toward us low and slow. We turned to face it in unison, as if hypnotized by the whine of its quad propellor blades. The screenwriter and I gaped. Pink hair gal whipped out her phone and started a livestream. Its shadow slithered over rows of parked cars, slinking down the alley like a shade in Hades, until it reached us, and for a brief moment blotted out the sun.

A cool breeze ruffled the weeds. I couldn’t stop blinking. I rubbed sunscreen and last night’s mascara out of the corner of my eye as I squinted at the noonish glare reflected in my empty coffee cup. The girl with the pink hair, her friend and the screenwriter were gone. I didn’t have a book by Stephen King and a stained productivity calendar. I was not the woman with an ex who ran a viral TikTok for frolicsome miniature cows. Or was I?

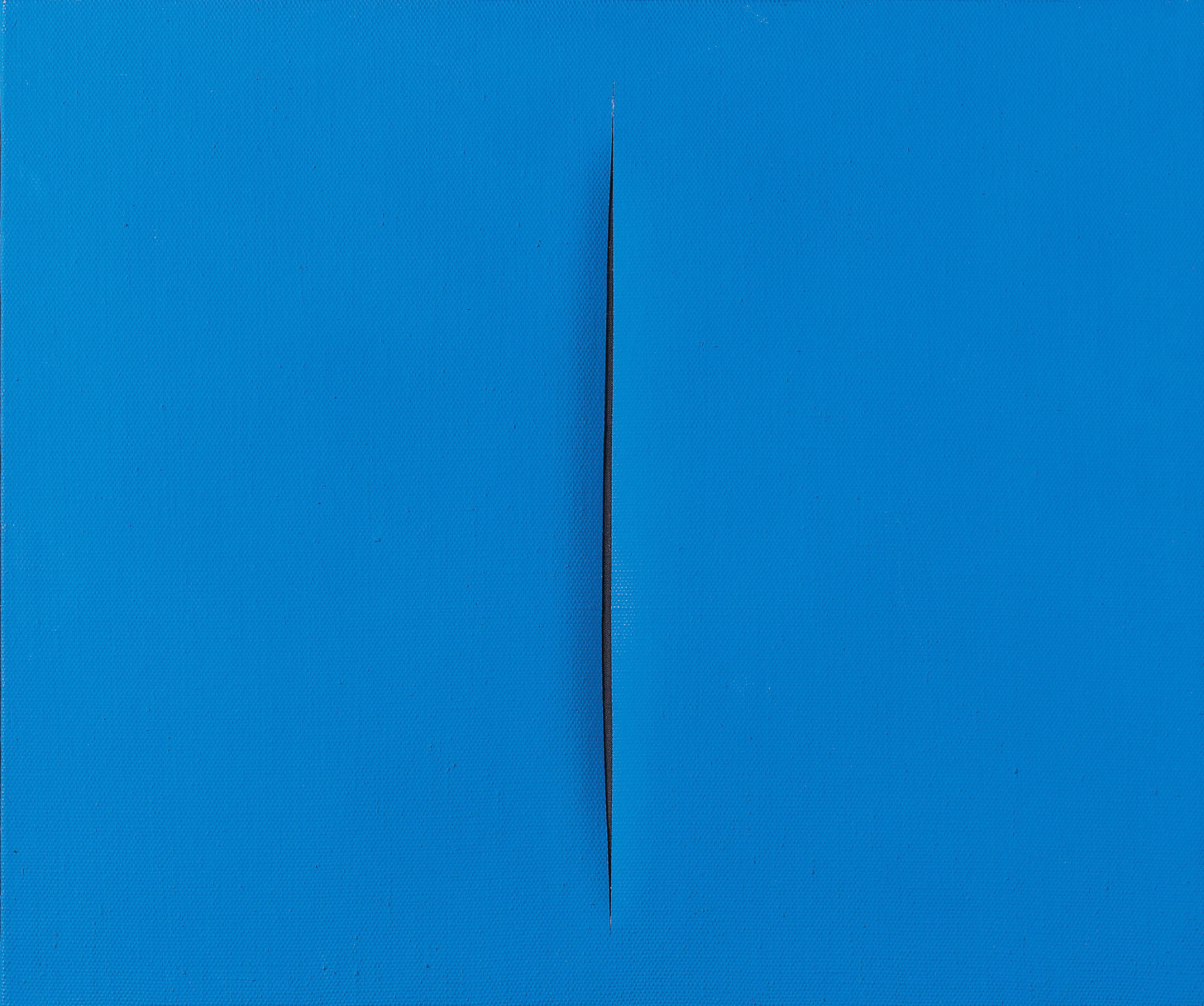

That sliver of a word, I, sits on the page like a vertical cut. That strange linguistic dagger is a portal, I thought. And I imagined all my I’s assembled, like a hall of mirrors, the I who has never chair-hopped like a seal for a potentially incompetent psychologist and the I who has, together in an infinity room with no fixed origin and no squinty pinpoint end. I was the girl with pink hair—swearing at the idiocy of others yet startled by my own unconsciousness, cursing both ends of an invisible finger trap I’d woven for myself—and I am always and forever reflected in her. I remember in my teens being so excruciatingly skinless due to an acid bath of inner criticism that in groups I often didn’t speak, and new acquaintances assumed I was literally mute. And I remember, ever so gradually, over the course of decades, becoming conscious of the trap that another, larger I had laid for myself, so insidiously and cleverly that now I’d call it one of my greatest teachers. That I would say that all my fruitless finger tugging with my so-called inner critic was actually training for a kind of steadfastness, a capacity to create and hold the distance from myself that I would need for real reflection. I was all of this and not this, a slippery dialectic of identity and difference that dissolved like gliding shadows into dark squiggles of pixels meant for you.

Wow I really love the casual surrealism in this.

"he snorted, gesturing to his car and the restaurant as if the world was his pasture." Yes!!!!!