A video clip has been making the rounds recently wherein Rick Rubin sits cross-legged wearing a t-shirt, with wisps of grey hair levitating from his temples. The interviewer, a coiffed Anderson Cooper, looks at him aghast and asks if he knows how to play an instrument? Maybe work a soundboard? Anything that would indicate an propensity to guide musical acts of all sorts to critical and commercial success, as Rubin has done for the past four decades? With Malibu-blue eyes, frazzle hair wafting, Rubin states that no, he has zero technical abilities of any kind. Then he lays out for us the one skill on which his entire career in music has been based: I know what I like, and I know what I don’t like. Rick Rubin has taste.

The way these words are said is so casually authoritative and enthralling that we instinctively know they’re true. Yet the simplicity kinda baffles the mind. I know what I like—sure Rudaddy, doesn’t everyone know what they like?

Truth is, they do not. Opinions are wildly contagious, and most people are catching someone else’s. It is very hard to be self-actualized enough to know, distinctly, what you do and do not like when you are confronted with a million and one musical inputs in the midst of a 12-hour recording session. And it is very hard to openly state, and on some level even admit to yourself, exactly what you like when what you like is non-consensus—which is when it matters.

You can’t DoorDash taste. What you truly, authentically like has to be mined in the slurry of raw perception. In another clip, Rubin reclines on a day bed in his recording studio listening to a jam, eyes closed, barefoot. The walls are white and unadorned. His every sense is tuned, bristling beard hairs undoubtedly picking up extra-sensory sonic textures. If you ask him what he likes in this moment (or any other, for that matter), he’s not going to give you a trivial answer. He’s absorbing information on a ridiculously high level, and filtering what he hears through a lattice of discernment no one else possesses. What we have here is a Rubinorganism: an absurdly refined nervous system whose senses and standards have been uniquely evolved via decades of such moments. This is how taste develops. Sensorial data is harvested, processed, evaluated, and matched in accord with a secret, ineffable framework to which only you hold the key. No one can do that work for you. It is up to you to refine your senses, to develop your own standards and capacity for discernment.

Yes, you could develop taste to please an algo, curry status, and/or climb the socially-prescribed ladder in your chosen field. Which is what most people do, and probably recommended if you want results that conform to existing expectations. But that kind of taste is adopted from an external source. Rubin did not say “I know what other people like” because it has nothing to do with his authentic taste. Of course a maelstrom of influences are pounding him from every angle, of course he is on many levels shaped by the codes of the worlds in which he is embedded—but that only makes his statement even more miraculous. In the face of immense expectations to which just about everyone conforms, he is absolutely unapologetic about relentlessly focusing on what he likes. That’s the source of his magnetism, that he can be such an integrated person as to care very deeply about the projects and people he works with, to be so tuned to the musical waters in which he swims, and at the same time, carve out a space to fully, precisely hear himself. If you are going after authentic taste, you have to actually know and hear yourself. The bombardment of other people’s tastes will never stop. It is up to you to claim space for your own.

The dark horse in Rubin’s statement is the word like. This humble monosyllable has wormed its way into our daily internet lives so thoroughly that it may seem banal at this point, but we should not forget its power. Across the web, our likes are farmed and monetized by multiple multi-billion dollar corporations—because taste has value. When you express taste, you elevate the thing you select, which takes effort and bestows a vote of value. Rubin wholeheartedly owns his vote, he puts the full force of his awareness and character behind his words when he says I know what I like. When you like something, it is worth considering on whose behalf you’re doing that work. You could blindly smash hearts in a semi-conscious TikTok fugue state, or you can bring awareness to your choice, however slight, as another step forward in the evolution of your perception and discernment.

At the root of every like is a grain of desire. Recall how hard it was to tell your kindergarten crush you liked them. How intensely vulnerable it can be to simply like another person, at any age. The little fires, the desires that move our tastes can be rather raw and tender. That’s also how you know you’ve found a vein of energy. You have to block out the noise, cultivate your awareness—and then be willing to feel.

*

When we think about taste, we often think of people who “have it,” but the getting and so-called having of taste is a real fucking journey that nobody seems to talk about and which never ends. I first experienced my own taste in contrast to the surrounding taste vacuum of the Math and Physics Building at Duke University. I was the only woman turning up at 8am for Differential Equations, and the only person with a visible aesthetic interest (somehow I trundled through roughly half of college intending to major in math and physics). One morning I walked along a wooded path between the bus stop and my staid brick destination wearing flowing sea-foam trousers and a slouchy lime green sweater, with several dense textbooks under my arm, and felt the dim awareness of a growing contradiction. I was generating a cloud of interests, curiosities, and obsessions of which I was barely conscious, and they had begun to reach a critical mass that conflicted with my circumstances. Some were visible, and others were tastes of a more delicate nature, like the rivers of questions I asked and which seemed to always flow outside the bounds of the disciplines I was supposed to be studying.

I took a year off from college to serve grits in a diner and detox from those early morning classes on Science Drive. As I poured coffees and gradually worked up the nerve to admit that I wanted to study art, I made a desk and replica Bauhaus shelves from scrap wood, and painted them both, along with the floor of my ramshackle attic room, glossy black. In those days, I associated art with the color black, which is obviously sophisticated, and glossy black house paint just screamed art to me. When I returned to school, I took Intermediate Sculpture because Beginning wasn’t offered that term (coming from the opposite end of campus, I had a lot of catching up to do) and for our first class project I doused my sculptural construction in glossy black house paint. When I placed this artwork on the table for critique my new professor was subtly horrified. I had unknowingly transgressed an invisible code of artistic taste.

Taste is synonymous with standards. But the interesting standards tend to go unsaid, and as we progress in a field they become so increasingly rarified that beyond a certain point they often can’t be verbalized at all. Locating them is a lot like driving bumper cars in the dark. The lesson in my collegiate artistic blunder was that there’s a feel for the universe of paints—once you begin to look, no two are equal—and all sorts of questions a sculptress might ask about the relationship of pigments and the materials to which they bind. But the particulars here are not so much of interest as the general, inevitable bumps and scrapes we incur as we come into contact with other tastes. Every point of contrast with someone else’s taste is a potential clue—maybe to the originality of our own, maybe to our present limitations.

A smart person on Substack whose name I can’t track down wrote: Skill is the floor, taste is the ceiling. We may be quite aware that we have a skill gap, but it is almost impossible to accurately identify our own taste-ceiling-problem. Discernment is a mega-factor in taste, but we can’t perceive our lack of it until someone or something provides contrast. For me the great value of school was in being exposed to people whom I could not have identified in my undiscerning state, and who blew gaping holes in my taste ceiling. To be in proximity to them over time, to gradually absorb their tastes through classes, yes, but just as much in offhand comments, stories and chats—I began to piece together my own taste from that expansion, building on what I liked, pushing off from what I didn’t, and letting the rest fall away. And the process has no end. Whatever taste you have, there is always more granular discernment to be gained, vestiges of old taste to level and smelt, and fresh information that ever promises to crosslink, crystallize, and sometimes even rearchitect it all.

Don’t try to develop taste to achieve a goal. Authentic taste is its own strange, unpredictable trip of discovery, and in creative work a goal can rapidly become a prison. With no background or training in writing, thirteen years ago I spontaneously started reading fiction like an OCD honeybee high on the sauce. Not just any fiction—I was surprised to find I had a capricious taste that made little sense at the time (I read nearly everything extant in English by or about the 19th century writer Nikolai Gogol, and expanded into a peculiar bricolage of experimental novels from 1750 to the present). It seemed like a ridiculous waste of brain cycles, but looking back it was an elegantly undesigned program of just the books I needed to read for style, structure, substance, a sense of history and ceiling-blasting that I only began to exercise as a writer years later. I could not have conceived of the outcome when I began; each book expanded my tastes another crack and organically led to the next. Goals may be very nice and motivational in the short term, but it can be helpful to remember that your present creative thinking is inevitably capped by a taste ceiling, which also constrains the goals you are capable of imagining. Oddly nonlinear as it may seem, the patient development of taste is an indispensable ceiling perma-remodel, enabling us again and again to go beyond ourselves.

Observing from the outside, we speak of people having taste as if it were some static possession, but from the inside, authentic taste is a practice, in flux, forever being shed and redefined. Since my stroll through the woods on the way to Science Drive, my tastes have molted and transformed a hundred times. Back then I loved the paintings of Kandinsky and Diebenkorn, German Expressionist woodcuts, and Matisse cutouts—being utterly new to art in those days, I needed the graphic style of those artists to begin to wrap my head around the mysteries of pictorial space. Most of my early tastes slipped away, except my fondness for Matisse, whom I revere only more but for reasons I couldn’t have guessed then and which continue to unfurl. That sounds pretty orderly in hindsight, but in practice it’s messy and even contradictory as strange new tastes continue to sprout while familiar, older tastes ripen and bear fruit.

I’m still learning to unreservedly love my tastes, all of them, from the most calmly quotidian to the wildest non-consensus zingers. I really do like math and physics and paint, astrophotography and dreams, weirdo experimental novels, the prose of Nikolai Gogol and W. G. Sebald, comedies with Will Farrell and John C. Reilly, and everywhere that art transcends its circumstances, whether it be an earthwork by Robert Smithson or a handmade cabin sculpture by Beverly Buchanan. It felt like a conflict and a loss to choose art but not math; I didn’t know that years later I would also become a writer, and that my essay about the mathematician Ramanujan’s dreams would unexpectedly find an audience and lead me forward into this delightful Substack realm with you. And who knows what comes next, I still don’t get how my grab bag adds up, but I’m seeking out the most delicious, evanescent edges of my tastes because they hint at heavens I can’t yet see. Each tiny honest yes I like this and no I don’t like that we declare as we express our authentic taste gradually and almost imperceptibly reveals another sliver of our gifts, and has been leading us toward their realization all along.

*

At a breakfast table overlooking Lake Geneva, Vladimir Nabokov liked to kick it with an espresso and read the tabloids, keen to relish the latest dramas. Indeed, the writer and butterfly-hunter of aristocratic Russian birth who slung sentences to the iciest heights of 20th century prose enjoyed News of the World with a croissant. Non-ironically. We tend to associate taste with fancy or some melange of cultivated, polished and highbrow, but it just ain’t so. You can express your authentic taste at the Dollar Store every bit as well as Tiffany’s, in the hush of the Metropolitan Museum of Art or wading through family nick-knacks in your uncle’s basement. Fancy and not-fancy are categories pre-established by other people’s taste, you may or may not find them useful in your unique parsing of the present. Really, high and low are distractions. Let it all go, and follow what you like.

Nabokov wrote a slim, little-known book on Nikolai Gogol (which reads like a transcendental fan letter) and in it elaborated a concept related to taste which I haven’t seen mentioned by anyone else. According to Nabokov, in older usage the Russian word poshlost—pronounced poshlust, with a stress on the o in the first syllable, ending on a soft t—meant in part trashy, cheap, smug, and precious, but with additional, quite subtle dimensions that set the word apart from concepts in any other language. “Obvious trash contains a wholesome ingredient,” wrote Nabokov, reader of the Enquirer, but in the worst trashiness of poshlost there is hidden duplicity. There “the sham is not obvious, the values it mimics are considered to belong to the very highest levels of art, thought or emotion.” For Nabokov, the tabloids are straightforward in their poshlost and thus benign. At the opposite end of the spectrum, there is nothing more loathsome than the pretentious poshlost of a “stirring, beautiful and profound” novel as it ponderously gambols around a pasture of seemingly elevated ideals, cloaking its trashiness with a veneer of high-mindedness. To this category we could add numerous Oscar-winning films and formerly-blue-check Twitter accounts—Nabokov even dared to detect a “dreadful thread of poshlost running through Goethe’s Faust.” Poshlost reveals his nuanced taste about what kind of taste to have. It takes discernment to like something for what it actually is, not what it pretends to be.

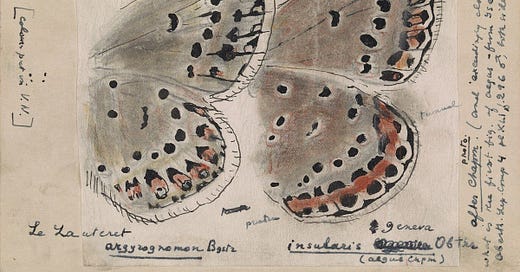

What Nabokov liked and very memorably did not like was itself an art of taxonomic specificity. He detested Freud, called sleep “the most moronic fraternity in the world,” and rigorously applied himself to a book-length experiment in precognition using his own dreams. While writing Lolita and other novels, he logged 200,000 miles of road-tripping across the US to pursue his tastes in lepidopterology, the scientific study of moths and butterflies. He preferred blue butterflies, and instead of classifying a catch by its chromosomes—as was accepted custom in the field at the time—he insisted on direct, visual observation of its genitalia under the microscope, and in this way discovered a host of new species, many of which are named after characters in his novels. He wrote volumes of the most intensely observed literary criticism I’ve ever come across, and has also been credited as the first person to suggest the happy face emoji.

You can follow Nabokov for a thousand pages, and he will somehow always evade the net. His tastes were as surprising as the capricious flight of his specimens, and at the same time reveal a secret thread in both the man and his work that could never quite be predicted. We return again and again to those whose tastes we admire—downloading their podcasts, opening emails, revisiting pages and refreshing feeds—eager to find out what they do and don’t like on a fresh day, here in the light of new events. And for good reason: Great taste is signal. As the sheer scale of our information ecosystem continues to explode in the hockey-stick direction, authentic taste will only become more captivating, and more valuable.

Preview image: A drawing of butterfly wings by Vladimir Nabokov

There’s been some wonderful writing on taste lately, and I’ve been particularly inspired by these pieces, which you might like too: taste from

and Notes on "Taste" by Brie Wolfson, and tweets on taste from @startingfromnix.

Really enjoyed your thoughts on taste as a ceiling, and the often invisible work that goes into developing it. Also, your writing on Nabokov--you've spent some time with him, and it shows. Cheers!

Made me think “De gustibus non est disputandem” isn’t a derogatory comment, it’s a statement of fact.