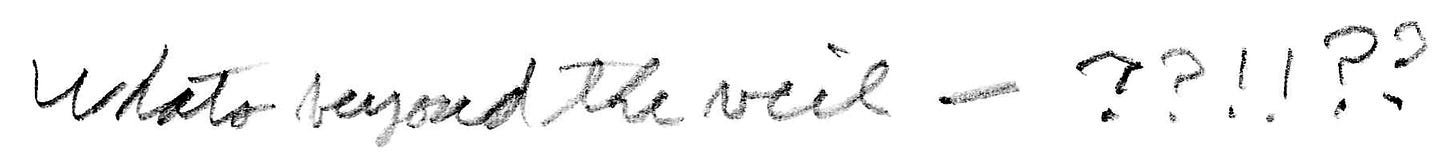

In the mid-2000s, a routine checkup revealed that my 84-year-old grandfather needed an immediate quadruple bypass heart surgery. This came as quite a surprise. The irony? He was a retired cardiologist.

Cardiology had been his castle and moat. After WWII, he lived in a tar-paper covered shack with his wife and infant daughter (my mom) while studying at Columbia Medical School via the GI Bill. In a photo from those years he looks dashing in a formal suit, hair wavy, with a faint chin-dimple and an aura of sensitivity that could be seen but never reached. You would never guess at his humble roots. His mother died before he could walk, he was raised (somewhat sketchily) by a single father. One summer his dad left him to camp alone under a tarp on a friend’s ranch in Arizona; as a teenager he picked melons to fund his prep for the Navy entrance exam. When he became a cardiologist, it was for him a scientific practice, a path out of generational poverty, a way of serving in the community. And a kind of imperial status.

As I grew up, we spent most holidays at the house he and my grandmother had built in Salinas, CA. I’ve never seen a home so overflowing with international art objects—hand-carved wood doors from Portugal; cloissonè vases he bought in the Forbidden City just after WWII; a display of Russian lacquer snuff boxes painted with a single squirrel’s hair. Nothing was expensive, but it felt untouchable.

During these visits I orbited silently, listening to him lead boring adult convos about geological trends in the Columbia River watershed or whatever. Occasionally, he’d make cutting remarks about my weight, as if it were either too much or too little according to standards he alone medically determined. And these standards—which I only ever saw applied to women in the family—flip-flopped with his whims, as if to drive home that there was no satisfactory female way to be, merely an endless series of fleshy mistakes to be punished and corrected. I was physically present at family get-togethers, but I wouldn’t say we had a relationship beyond that.

After his quad cardiac event, I heard about his healing through dribbled mentions from other family members. But I didn’t see or speak with him until Christmas at my parent’s house that year. I was older then, living in East London, scraping through a PhD in art. I broke from my tradition of dull-but-appropriately-tolerable X-mas prezzies and gave him a t-shirt from the London tube with “Mind the Gap” emblazoned across the chest. As quickly as it had been opened, the shirt dropped back into the box—he was deeply unamused. What is with my impish gift? I wondered to myself. Only now do I recognize that on some barely conscious level, I’d sensed a subtle shift.

In a totally uncharacteristic move, the next day he laid out 20 rolls of film on the dining room table. After a long illness, his wife, my grandma Scottie, had passed away the year before, and in his post-surgical recovery he had begun to downsize. He wanted to filter through this mess of photos the two of them had made on their travels, to keep a portion and throw the rest away. I’m a sucker for vintage photos, so I joined him.

He thumbed through pics of exotic plant life, crumbling ruins and golden Buddhas from distant locales like Jordan, Myanmar, Maui, Tibet. The more he flipped, the more frustrated he became. Almost no one was in these pictures. Maybe 1:40 included a human he recognized—usually a posed photo, with he and my grandma or their friends against a new backdrop. He spoke a bit about the procession of tour images, a few remembered facts and points of interest. But in the silence hung the question of what remained.

After his heart surgery he began to change. To be closer to his son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren, he moved from Salinas to a tiny house on a cul-de-sac in Grants Pass, Oregon. In that move he let go of much of the art he’d collected, and began to make his own.

First, he took classes in Computer Art. And then, in his mid-to-late 80s, he began to turn wooden bowls on a lathe in the shed behind his home—several of which were collected by a Japanese bank. There tends to be a competitive trend among wooden-bowl-turners to shave the sides and lips of their bowls to the absolute thinnest width wood will bear. He didn’t care about this status game whatsoever, and gifted me a slab of a bowl with grain like molten honey and inch-thick walls. He explained that he preferred the presence of imperfections, and in turn, his work exuded an aura of matter-of-factness with style. When a knot fell out of wormy wood, he filled the gap with clear resin and crushed gemstones.

Usually I stayed at my uncle and aunt’s place when I visited, but for reasons I don’t recall, after grandpa turned 90 I went to stay with him. On the first day of my trip he’d planned to have me weed his tomato plants, but the weather gods intervened and it rained. That morning we sat in his little living room, listening to the soft, syrupy patter of the rain, not really knowing how to be with each other without an assignment. We talked about the day and his mislaid plans, when he diverged and began to tell me a story from WWII.

Wait just a moment, I said, retrieving my laptop. While he spoke, slowly pulling at threads, I typed. By the time I left a couple days later, he’d dictated 10,000 words of his life story to me, which spawned another trip and another 10,000 words.

His memories of WWII were vivid. From 1942 on, he’d served as a gunner on the USS Indianapolis, a heavy cruiser in the US Navy—pictured above—and saw combat across the Pacific theatre. But in May of 1945, he decided to leave the Indy to retrain as a fighter pilot. A commanding officer rebuked him, pointing out that fighter pilots were far more likely to be killed than gunners—even and especially in training. But he wouldn’t budge from his decision, and promptly left for flight school. Just two months later, a Japanese submarine torpedoed and sunk the Indy in shark-infested waters—by many accounts the worst sea disaster in Navy history. All but 300 of the 2,000-man crew lost their lives in this surprise attack, including many of his friends. In other words, his intuitive pull to aviation saved his life. Only years after he told me this story did I connect that in Hindu systems, the heart chakra is linked to the element of air.

Some things didn’t change. He got angry when I cooked meals that were too healthy. When I asked him about his Computer Art classes, he refused to disclose what went on at those affairs. Although he did, a month or two later, send me a couple of unmarked manila envelopes with 8x10 prints of images he had made. In one, my favorite, a shadowy island rises up from a lake with wind-whipped waves that gleam like facets of a fluid diamond.

In the spring of 2012, I sent him the manuscript of his life story, and he sent it back to me with corrections and additions. With this new mailing he included 13 additional pages of handwritten notes in his spidery, tilting cursive.

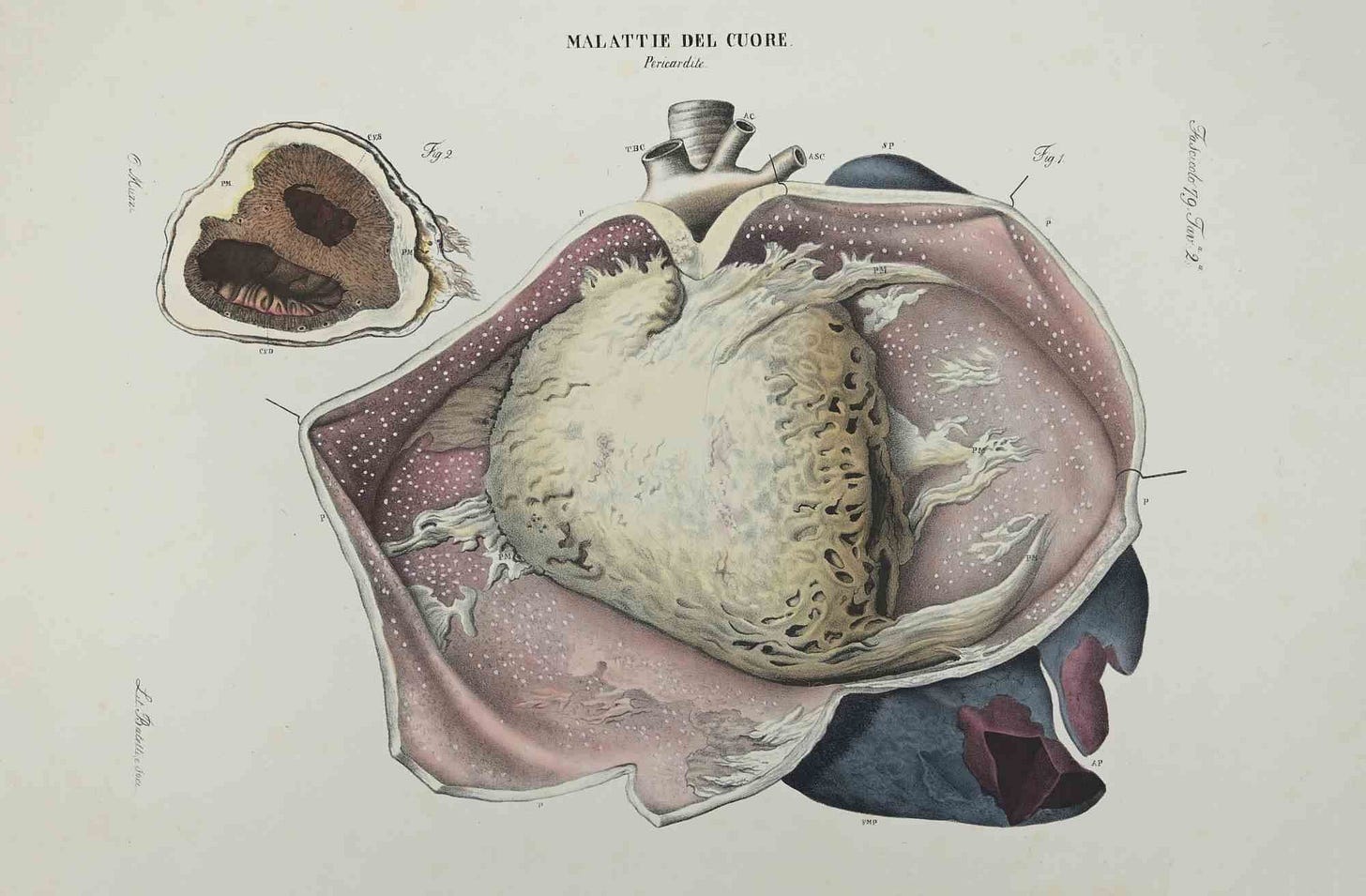

The pages begin with a timeline. They list the concrete facts of his childhood and adult life—much like the objective details he conversed in and photographed on trips, but here they had been unearthed from the loam of his own life. Then, on the second-to-last page, he begins a fresh sheet with the heading “Summary.” On this page he writes, for the first time of his lonely, detached childhood. In the following 16 lines, he notes the lessons he learned at each stage of life, some of which include: from the Navy, discipline and self-assurance; from cardiology, judgement and perspective; in retirement, humility and the value of relationships above material things. And then, as succinctly as it begins, his summary ends with this question:

The day before he died, my brother called me and asked, Are you with Grandpa? Because I just talked to him on the phone, and he said you were there. That afternoon I was in Los Angeles, and I hadn’t been to see him for a few months. So I called him. He was only partly coherent, fading in and out. I thanked him for sending me his timeline, but he didn’t believe me.

And then, toward the end of the conversation, I said again, slowly and clearly, Thank you for sending me your timeline. It’s a treasure.

You’re very welcome dear, he replied.

Then he paused and said, We should celebrate.

I agreed of course. And I also wanted to know what he meant.

When I asked, my question dissolved into his delirious cloud-consciousness, as if he had expanded time itself. Maybe I really was on the couch in his little living room, or at a dining room table with old photos. I could hear the metallic creak of the chairs in the kitchen with Spanish tile where he and Scotty raised three children, sold years ago. We wondered what we were celebrating, but it didn’t matter. We were happy. And then it was time for him to go.

I’ve been writing down my dreams for well over two decades, but I rarely dream of him. I can only recall a few in total, so when they come, I take note. One arrived about a week after his death: In the dream I walked through the hills above Los Angeles on a bright June afternoon. As I turned a bend, we met on the trail. We were both so surprised to see each other. Though he was still in declining health, he said, “Well, we should break out the champagne!” I saw a lightness and joy in his presence that I realized had always been part of his spirit in life, only now it had come to the fore. And I felt a sense of peace.

Last November, more than eleven years after our last nocturnal rendezvous, I dreamed of him again. In this dream I stood on a ocean wave, as if it were a perfectly natural thing to do. The wave whisked me across an expanse of empty sea, until it suddenly brought me face-to-face with him. This time I was surprised, but he was not. He simply smiled, his cheeks red, his white hair long and tousled.

I don’t even try to interpret dreams. An interpretation implies a porting of meaning from one language to another—which is already a mistaken premise—as if you could ever translate a dream into sensible, non-puzzling strings of words as you do from, say, Spanish to English. Oh no, it doesn’t work like that. A dream, like a life, is a perpetual engine of questions.

The current of my mind keeps returning to that second dream moment. To seeing him, after all these years, face-to-face. To his knowing smile, and how it always hinted at a great deal more behind it. To cardiology as the study of the heart, and how the full arc of his life encompassed that study in ways I am only beginning to understand.

In the West, it’s common practice to cast the brain in the role of bodily-commander-in-chief. But discoveries show that more information is sent from the heart to the brain, rather than the other way around, as is so often assumed. Embedded within each of our hearts is an intricate network of neurons and neurotransmitters—the same stuff as our brains. This neurocardiac circuitry allows our heart to act independently of our brain, to learn, remember, make decisions, feel and sense. As the nascent field of neurocardiology has shown, the heart has a mind of it’s own.

This should not be news. We’ve known for thousands of years that our hearts are intelligent. Many classical Greek philosophers—Aristotle included—considered the heart to be the seat of thought, reason, and emotion, and the brain a mere appendage. In biblical Hebrew, the word lev meant both the insubstantial mind and the very physical organ of the heart, because, however foreign it may seem to us today, in those cultures the heart and mind were one. Similarly, the Chinese word xīn is often translated as heart-mind, and it should come as no surprise that ancient Chinese philosophers also viewed the heart as the seat of cognition. In Chinese medicine, the heart is the origin of shen, our spirit consciousness, and the home to which it retires every night in our sleep.

When I recall what I experienced from him growing up, I don’t know what better to call it than love from a blocked heart.

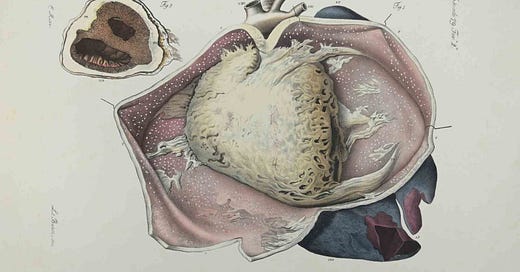

After the surgeon cracked his sternum open, after they grafted four new paths around decades of calcified coronary plaque and his blood could flow again, as it hadn’t in years, is it any wonder that his being changed? Is it any wonder that he would begin (with a freshness I’ve never seen from someone in their mid-80s) to learn, remember, make decisions, feel and sense—from his heart. To love in new ways.

What I did not know, back in 2012, was that his heart was opening mine.

I’m surprised by how little I know about the heart. Yet the textbooks say it’s the first of our organs to develop. In the month after conception, the clump of mesoderm cells that will become our heart first emerges within our embryonic head—a detail the ancient philosophers might have appreciated. As this tissue differentiates, it moves down into the thorax, forming a tube. And in a process that is still not understood, this thin cylinder of tissue begins to spark with spontaneous electrical activity, causing the proto-myocardial muscle in its lining to jerk and twitch. At first these movements are seemingly random and irregular, until they gradually coalesce into the familiar pulsing contractions and expansions of the heartbeat that will accompany us for the rest of our lives.

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places, wrote Earnest Hemingway. This is true. But there’s more.

His stories, those convos—they weren’t just words. They were acting on me in ways I can hardly describe.

Somewhere behind the cantankerous, imperial grouch I met a real heart connection, one that sure didn’t resemble any Hallmark cards. It was like air. It was like a cool gust fanning the deck of a heavy cruiser sailing off the coast of Japan eighty years ago, sweeping from his stories into my days. And very slowly, almost imperceptibly, I changed.

All the dagger-shaped comments, the inexcusable crap he said and did, those were contractions. At the end of his life, he began to slough them. And I started to slough their residue too. My own heart had been contracted, terribly cramped by my personal, familial, and cultural patterns of limitation. But that air, it ever so gradually started to dissolve them.

And as my heart expanded it filled my art and writing with great big gusts of psychoactive atmosphere I could barely fathom at the time. His story in part inspired my first short story, Boy With Frog, published by The White Review a few years later. And without any conscious inkling of these connections, I built a ghostly one-and-a-half story sculpture on an abandoned airfield, titled A house made of air and distance and echoes. Even though I didn’t understand it yet, in those and all the works that followed, I couldn’t stop a transcendental vibe from breaking through. I couldn’t pretend any more that this plane is the only one. The heart is so subtle. We notice the movement of air by the impression it makes, by the tilt of a palm tree and white caps at sea.

EXQUISITE. You are one hell of a writer. Bet he’s proud as punch from beyond the veil.

This is amazing. What a beautiful tribute.

"A dream, like a life, is a perpetual engine of questions."