Echo's Loom

creative work (and spooky dreams) from the inside out

Earlier this year I had a solo exhibition at a gallery in Los Angeles. There’s a convention to the way art exhibitions go—you make artwork, the gallery sends out an invite and press release, people come to the opening. Maybe you have more events, people visit the show, and then it closes. Things are sold, or go into storage until their next outing. You move on, and do the next show. But I’m a little bit too disagreeable to stick to the standard format. So I thought it would be fun to give you a tour of the show. To share a few ideas behind it, with a slice of what it’s like to make creative work from the inside out.

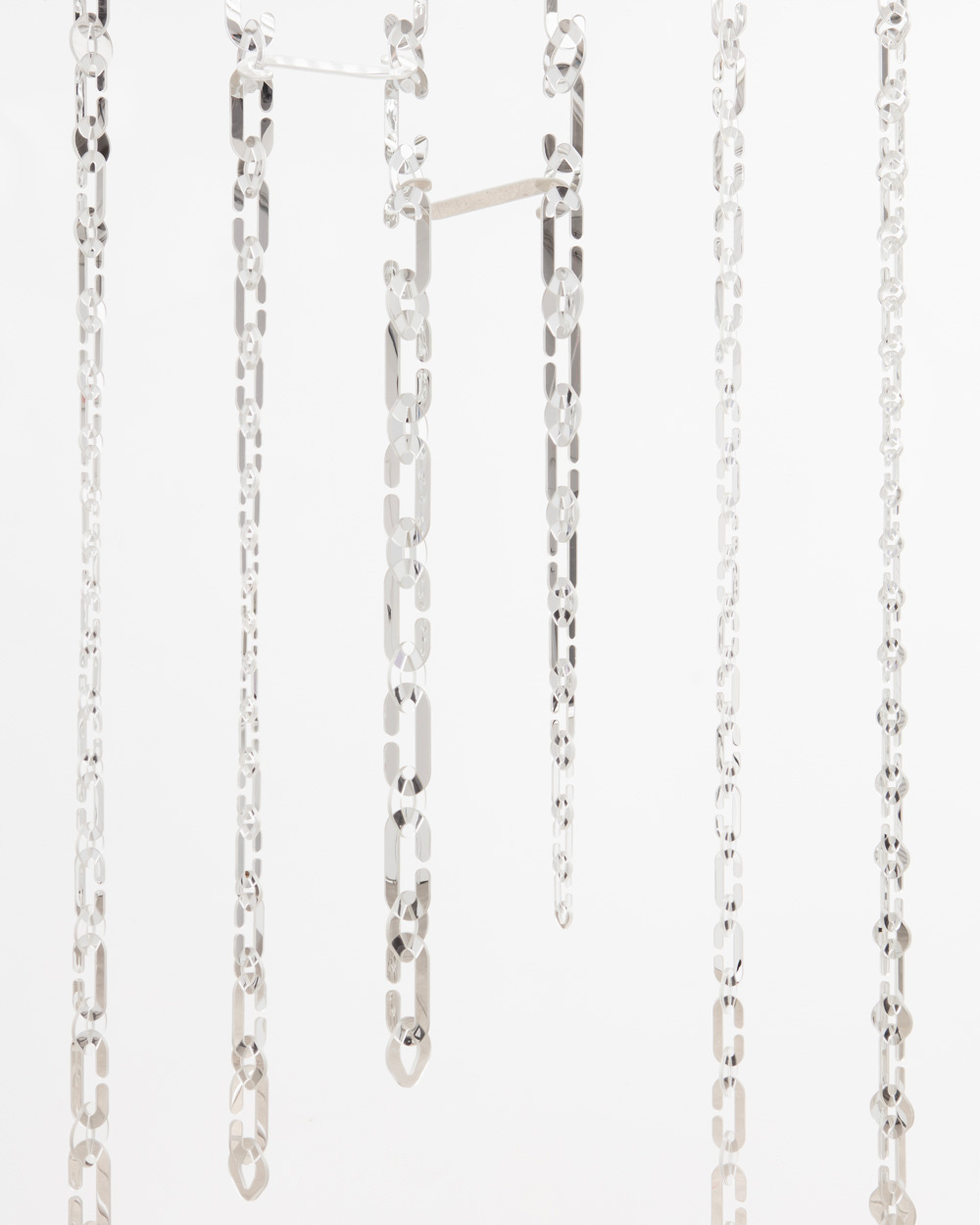

The show was called Echo’s Loom. In the center of the gallery hung an architectural sculpture made from 2,000+ pieces of mirror woven into lace.

When I mention lace, people imagine doilies and curtains. But the stuff is infinitely more varied. Like any mobile technology, lace has sprawled across the globe, and everywhere locals made it their own—there’s a type of pastel-colored lace unique to Graz, Austria, a lace made from palm needles in Amazonia, from silk in Malacca, Malaysia, and from aloe fibers in Albissola, Italy.

Lace is broadly defined as an open, web-like fabric. Its origins can be traced back to the ancient practice of making nets—the many varieties of lace are actually a special type of net. As soon as humans figured out how to twist plants into cord, we started making nets to catch and carry tasty stuff like game and fish. Because of their ephemeral nature, it’s hard to place early nets in the historical record, but we have a few hints: 23,000 years ago, artists in the region of the now-Czech-Republic pressed nets of knotted fiber into wet clay, preserved to this day in shards.1 Egyptian paintings feature garments of a fine net mesh, Homer describes veils of net made from gold, and Isaiah mentions “they that work in fine flax and they that weave networks.” Up until the late 19th century, in English the words “lace” and “network” were interchangeable.2

Because handmade lace is exceptionally labor intensive to produce, more than any other form of weaving, it is a network not just of thread, but of time, attention, and value.

The scale is tough to gauge from photos, but to give you a rough idea, the sculpture ate space, clocking in at about 23 feet long, 17 feet wide, and 11 feet high.

Each piece of mirror was cut in my studio with a hand-held CNC. The term CNC is short for computer numerical cut, which is a fancy way of saying, “I give the lil computer inside my tool a digital file, and then it moves a router bit to precisely cut that shape.”

Most CNC machines have a fixed bed to which you attach your thing-to-be-cut, and the router bit runs around within the bed, controlled by servo motors (or, in more complex setups, a robotic arm does an Edward Scissorhands dance).

Instead of full automation, my CNC setup is like a router video game—it is literally a router with a computer attached, plus an onboard camera that senses its position in space. The screen displays a dotted path to slide the tool along (a bit like PacMan) while the router bit moves precisely to cut the exact shape of a given file. The camera-computer-human combo works kinda like a cyborg—amplifying both hand and machine. Using it becomes a slow-moving, insanely loud, and plastic-smelly meditation that melds physical and digital worlds in a single cut.

It is pretty well acknowledged that the histories of weaving and computing are deeply intertwined. Back in 1804, French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard debuted the automated loom—a hulking timber contraption for weaving, as if somehow a tree and a spider had mated—and forever changed the production of textiles.

In essence, a Jacquard loom is simply a loom controlled by a long chain of punch cards. Before this bad boy hit the streets, a weaver had to scrutinize a textile pattern line-by-line and laboriously raise or lower each thread by hand. For the first time, Jacquard’s punch cards encoded the sequence of a textile pattern’s rising and falling threads in a kind of binary external memory, and automated the action to boot.

Jacquard’s punch cards inspired Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a machine designed to perform step-by-step calculations (i.e. programs) and an early prototype of the computer (Charles even carried punch cards around London in his pocket for the inspo). Ada Lovelace, Babbage’s protegé-accomplice, famously stated that the Analytical Engine “weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” And in 1890, even further inspo’d by the punch-card-as-external-memory phenomenon, the American inventor Herman Hollerith devised a punch card system to automate the super-tedious task of counting the US Census (and in the process founded a lil company that would come to be named International Business Machines). By 1937, IBM generated 5-10 million punch cards per day, a continuous blizzard of card stock fed to the hungry electronic computers of the early twentieth century, plus all sorts of other data processing. And punch cards stuck around as the default method for loading data or programs into computers pretty much until Michael Jackson moonwalked in the 1980s.

It is much less well-known that Jacquard’s second major invention—launched roughly one year after his automated loom—was a machine that automated the making of nets.

And here’s what I haven’t seen mentioned elsewhere: Lace isn’t merely linked to computing, it’s the OG web.

Lace as we know it today bubbled up from a ferment of medieval net-making across Europe in the 1500s. It rapidly became so fashionable that euro aristocracy repeatedly passed laws to limit the amount mere commoners could own, and so valuable that it’s cost rivaled that of gold or jewels—which gave rise to flagrant black markets, with lace smuggled across borders by dogs and in corpses.

Back then, if you could afford it, of course you got your picture did in lace: Queen Elizabeth commissioned hers in a galactic, spangled froth that foamed around her face from cleavage to crown; Christian IV, King of Denmark, sported a sleek lace ruff; Pope Clement XIII an exquisite lace chasuble and flounce (in other words, Catholic gear with flair). The exorbitantly expensive lace worn by the wealthy and powerful was made by women of all ages and backgrounds, across the countryside and cities alike—by girls from the age of 4 onward packed into tiny rooms and forced to work 10 hour days, exploited orphans, women of leisure, rural lacemakers converting their time into currency—and countless others of whom we know little. The extraordinary ingenuity of these networkers resulted in a craft that became ever more intricate, delicate and hyper-connected, almost virtual, giving rise to forms like punto de aria, a type of 17th century geometric lace so insubstantial that it translates to stitches in the air. And lace dematerialized still further. It gradually dissolved, in the wake of Jaquard’s second invention and the Industrial Revolution, into the ever-widening nets yet to come: the world wide web and the internet, the cartographic enmeshment of our globe in GPS, and today’s neural nets.

At the end of 2023, I dreamed of my grandmother. She’d passed away 19 years prior, and in all that time she hadn’t appeared in my dreams. The dream took place in an open space with dim, diffuse light, just her and I, nothing else. Shadow pooled around us on all sides, bleeding into darkness. I couldn’t see more than a few feet away. She looked ancient, but with no loss of energy or her powers. I remained unperturbed by the ambient weirdness of the setting, and felt only reverence in her presence. She held out her left hand and showed me the back of it, both strangely tan and intensely age-spotted. A tiny piece of lapis lazuli had been set into the middle of her hand, a deep-blue stone a bit wider and twice as tall as a single grain of wild rice. As she showed me her hand and the stone, she asked, would you make me a piece of lace to cover it? She draped a swatch of white filet lace—a fine net mesh—over the area she wanted covered, extending from her wrist to her fingers. With zero hesitation I said yes, I would do this task for her, and that I already had several pieces of lace I could use to begin.

When I woke up, I felt impressed by this dream, and had no idea what it meant.

My grandmother’s maiden name was Alma White, though everyone called her Scottie. She grew up in a white clapboard house her father built on their homestead farm in Nebraska, thirty miles from Broken Bow, the closest scrap of a town. Alma means nourishing, soul in Latin, but I wonder to what extent she received nourishment as a child of the Great Depression, because she only ever maxed out at 5’2” in shoes. The most advanced degree her mother allowed her to pursue was in nutrition, which she went for, and to my knowledge she was the first woman in her family line to go to college. You could feel the remoteness of the high plains in her spirit, blasted out by the cavernous dome of light that crowns Nebraska’s ocean of corn. In 1946, she met my grandfather when he popped open the top of his flight simulator at the naval aviation school in Corpus Christi, Texas. For the next few weeks she taught him how to fly via instrumentation in a WWII-era simulator called the Link Trainer. I don’t know anything about the improbable chain of events by which she extricated herself from the cornfields and ended up thousands of miles away in such a coveted job, only that she was a member of the WAVES—or, Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, a special unit of the US Naval Reserve—and that six weeks later my grandfather proposed over crêpes suzette. After the war, sponsored by the GI Bill, they moved into a tar-paper-covered shack north of NYC so that my grandfather could study cardiology at Columbia Medical School. My grandfather once mentioned that my mother, by then just 18 months old, got curious one afternoon about a bubbling pot on the stove, and in response Scottie smacked her on the head with the heel of a shoe. This seemed totally normal to my grandfather, but to me exposed a tendency I also bore the brunt of, a punishing hand passed down the generations.

I know so little about her life beyond these few sketchy outlines: By the time she reached thirty, her wavy red hair had spontaneously blanched pure white. While my grandfather practiced cardiology in town, she raised their three children on a sunny hillside overlooking the fields of Salinas, California. She gardened, canned her own mincemeat, and fundraised for their church; she had a talent for sewing and shrewd investments. I still treasure a few pieces she made by hand—a purple velvet cape, a flowing grey silk coat with black velvet tuxedo trim, a crushed velvet blanket with mauve lining cooler than anything you could ever find at Urban Outfitters. She had the diy resourcefulness of a homesteader, but with a soft spot for velvet, clean lines and glamour. I can still see her at the yellow formica counter in their kitchen—a petite, coiled steel spring sheathed in a cream silk blouse and burgundy slacks, issuing a few curt updates on a call with her stockbroker, Len, before returning to slice grapefruit for her guests. No one crossed her.

I don’t recall her ever making lace.

By the end of 2023, I forgot the dream.

I sincerely wanted to fulfill whatever task it had saddled me with, but I couldn’t figure out what to do. By then I knew better than to try to force it, so I moved on. In the months prior to my grandma’s nocturnal request, I’d been making a series of digital lace artworks, but I’d stopped the project due to health issues, then abandoned it as a dead end. Almost an entire year later, in the late summer of 2024, as I worked through painting ideas for Echo’s Loom, it dawned on me that a batch of lace tests I’d made and discarded the previous year would be a perfect starting point. It took me even longer, until months after the show was finished, to finally notice the link—that of course, all along I’d already had pieces of lace to begin, exactly as I’d told her in the dream.

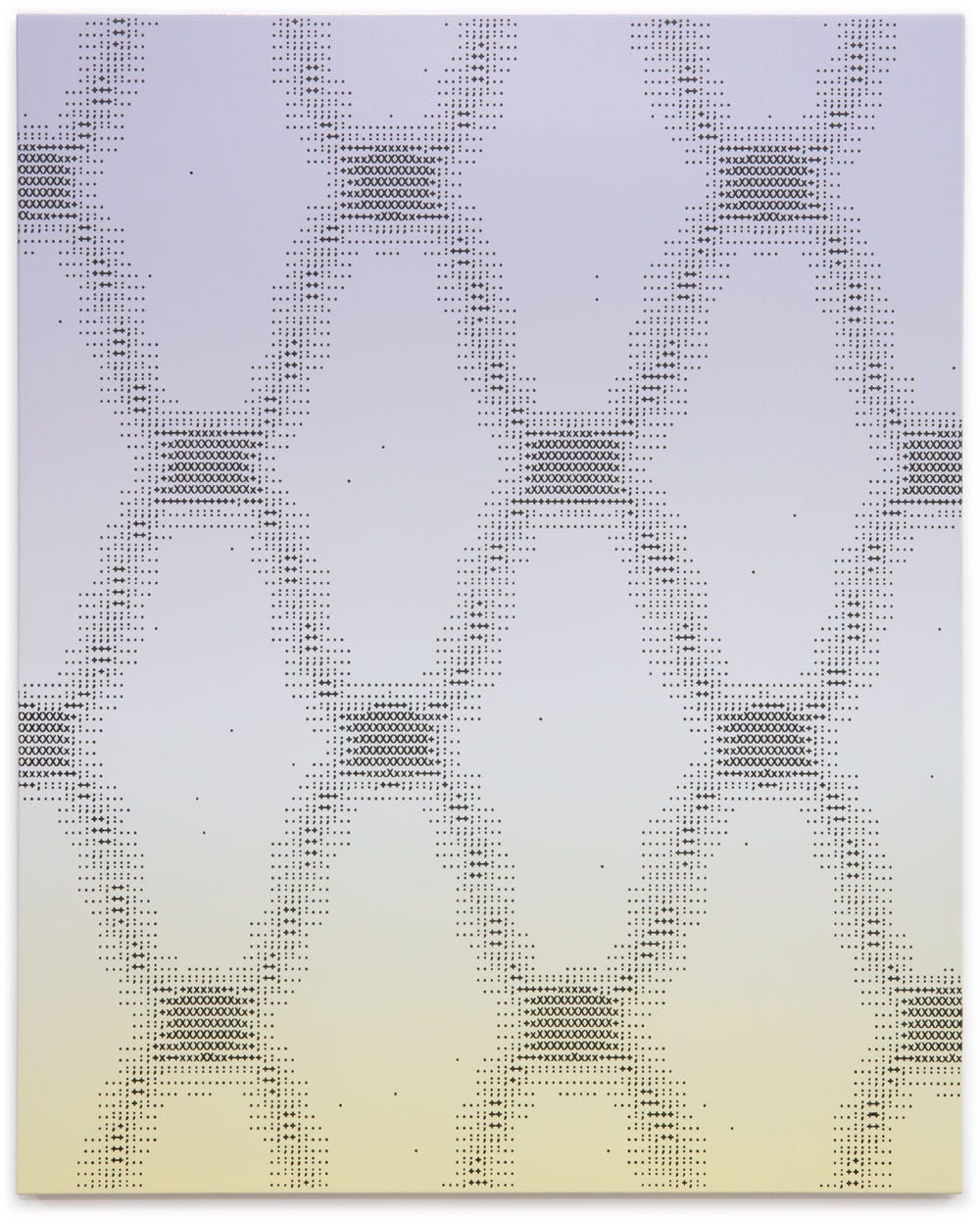

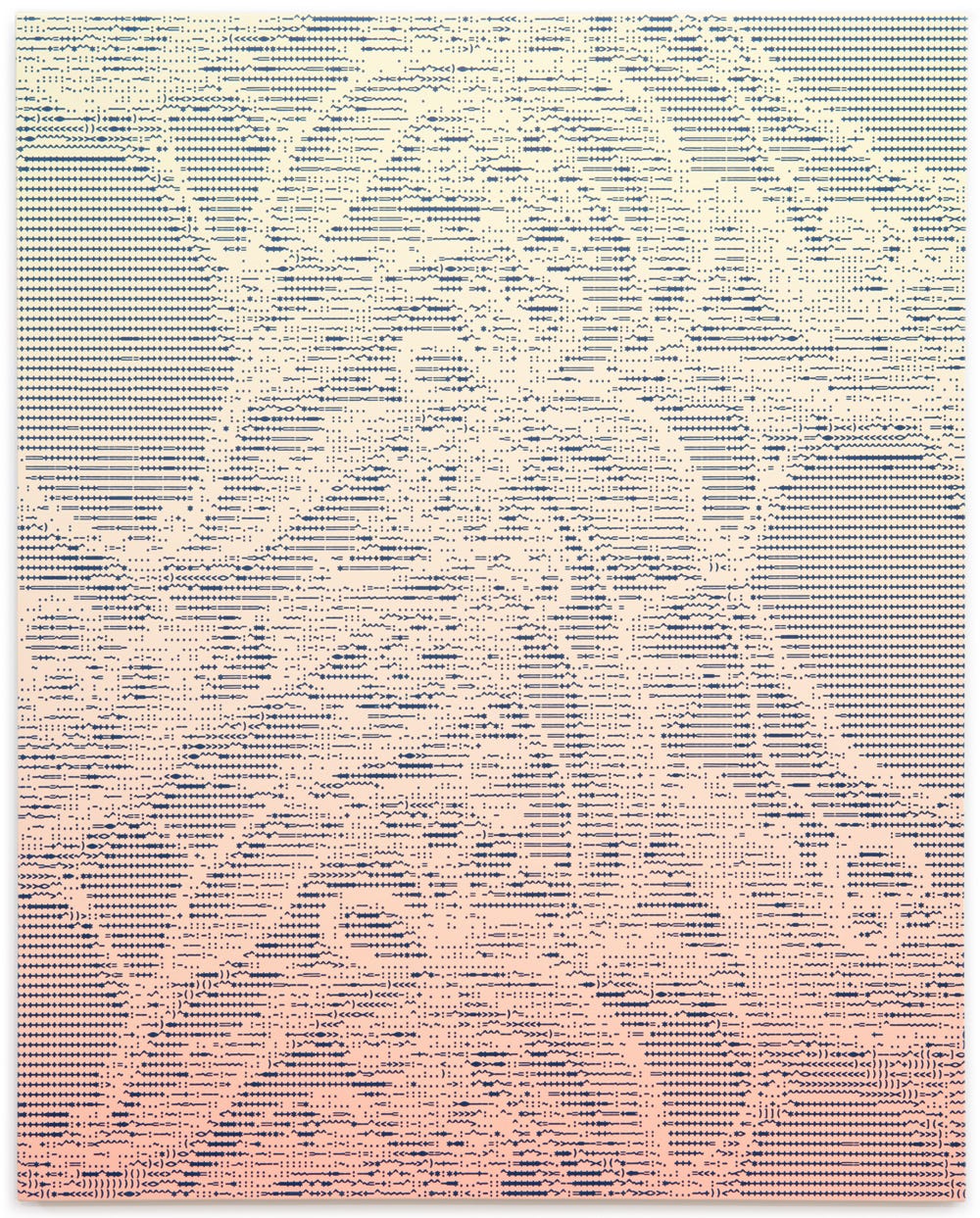

Each painting in this series is based on lace. Some are derived from AI generated lace, others from historical patterns or nets. People ask me if they’re prints—they’re not, it’s just good ol’ paint on canvas. They look kinda perfect, as if they happened to teleport from an ethereal realm into this finished form, which is pretty annoying because it takes me hours upon hours to build them up.

First, I fill in the weave of raw canvas to create a flat surface, which takes about 10 coats of a special paste and primer, with a round of sanding between each coat. Then I spray about 15-16 coats of super-misty acrylic paint to slowly generate a seamless top-to-bottom gradient. In between those interminable coatings, sandings and mists, I cut vinyl stencils with the images—the stencils are cut by machine, but have to be “weeded” by hand—each of the thousands of marks in these paintings got individually plucked out with a scalpel. After I finally get the stencils onto the canvas (the trickiest and most anxiety-inducing phase), I airbrush another 8-10 coats of acrylic paint through the stencils, plus a ton of other details I’m glossing over. I’ve listened to a lot of podcasts.

I’ve only ever had one other dream encounter with my grandmother, from way back in the spring of 2002. At the time, I lived in Winchester, England, mid-way through an MA in Sculpture—that year was my first real intro to contemporary art, immersive and intensely formative. Though simple, the ‘02 dream was so vivid I could never forget it: I dreamed I was in the living room of a house that seemed quite nondescript, except for very large plate glass windows that looked out onto a barren, rocky, and somehow frigid landscape—remote as an alien planet, with no vegetation or sign of life as far as the eye could see. Suddenly my grandmother appeared outside the window, her face blue, seemingly unable to breathe and frantically gesturing to me for help. I rushed to open a door and let her inside. After she came in, she thanked me, and went upstairs to warm up and rest with my grandfather.

When I woke up, the dream stood out as particularly memorable, but the shock came when my mom called later that day. She said my grandmother had suffered a serious stroke, and that she’d died and been resuscitated the previous evening in Salinas, CA. In UK time, that was equivalent to the wee morning hours, so it could well have been simultaneous with my dream. This all unfolded totally out of the blue. Until then, my grandmother had seemingly been in good health, and I hadn’t spoken, emailed, or in any way been in touch with her for months.

The next time I saw her, at my parent’s house in the fall of that year, she was deeply compromised by the stroke—frail, unable to say more than a few words, and almost completely reliant on my grandfather’s help for daily life. After I came in from the airport, I sat down next to her on the couch, wanting to ask her a million questions, but she couldn’t speak. She just reached out to me with her left hand, grasped my wrist with an almost superhuman strength, and didn’t let go. We sat there like that, my hand held in her iron grip, with me telling her how much I loved her, then lapsing into silence as family chattered around us, for half an hour.

I don’t know what passed between us in that dream or on the couch. But I do believe, in some way it would never be possible to fully name, that it was my initiation into art. When I think back on that dream, the gravity of her need woke up a capability in me that I didn’t know I had. It’s as if the dream said: Here we are at the boundary between the known and the unknown, the living and the void. You can just open the door. And I did.

There’s this idea in movies, TV, and the popular imagination that artists at work sit perched before an easel in a crisp white smock channeling divine inspo directly onto canvas. Which could not be further from the truth. Making anything physical and real and new to you is inevitably a total mess.

While making this show my external hard drive failed. For reasons I still don’t understand, Photoshop stopped opening. I couldn’t get my vinyl cutter to make cuts at the mm accuracy I needed, and while I tried every possible fix I wasted 150 feet of vinyl on mistakes. I called the vinyl cutter support line so many times the technical guy knows my name. I bought the wrong size cutter blades but only discovered that after I had them FedEx next-day shipped. The special mirror glue I use to turn single-sided mirror into double-sided got weirdly chunky, then stopped working. When I went to pick up more glue on the day before Thanksgiving, the wholesale guys gave me 5 free cans because they said they probably sold me expired product. After another round of trial and error I realized it was simply too cold in my studio for the glue to set properly. I got 3 space heaters going, but still couldn’t keep the temp high enough to get a full sheet to set, so I had to discard a bunch of pieces per sheet and/or fix them together by hand. And then, on the second-to-last day of cutting prior to installing the show (a Saturday), my CNC motor died. I couldn’t buy a replacement in time—praise be to Anderson Plywood for loaning me their display motor so I could finish the sculpture.

Art shouldn’t happen. It’s never a good time. Something is always breaking or misbehaving. Atoms never quite go where you tell them to—which on rare occasions opens up miraculous new avenues to explore, but on average just causes head scratching, or worse. You choose to do it anyway. You transgress—you disregard the sensible timelines, the typical uses of a tool, the need to eat square meals and dress presentably and whatever other conventions people expect from you. You dare to defy the comforts of normality.

And when it works—when you hang the last piece a few hours before the opening, haul your cardboard boxes of tools away and stand back—all of that falls away.

Photographs are like Plato’s cave-shadows compared to being in person with a real artwork.

What you can’t see in these images is the way your movement around the sculpture makes these long, silvery mirror strands morph: As you approach and turn, they bounce back a play of floor, ceiling, and gallery walls that shifts around you. The average mirror is straightforward. It’s set directly in front of you, and reflects your image directly back. But this sculpture is more like an inverse kaleidoscope. Because the mirror pieces are set at alternating angles—never head on—they reflect back the environment in all directions. Looking into the sculpture, you see everything around you fractured and remixed in its immersive mirror-fabric. And when you stand in front of it, splayed out for twenty feet to the right and left, you see yourself reflected in a hundred different facets, sliding into and out of view with every step.

In a nod to Jacquard’s chains of punch cards, here lace is simplified to a binary—alternating hooks and loops. The vertical chains of hooks and loops are connected by longer horizontal hook-pieces that run across the top of the sculpture, and in diagonal dash-lines downward, echoing the timber beams that flow across the room and diagonally up. Instead of a traditional lace pattern, most of the vertical chains have a subtle pulse. Rhythmically increasing and decreasing in both size and complexity, each of these strands encodes a wave.

Echo’s Loom is also a reference to the Greek myth of Echo. In the ancient author Longus’ account, Pan—the lustful, rowdy, half-man and half-goat god of the Arcadian wilderness—envied the nymph Echo’s musical ability and fell in love with her. Pan kept hitting on Echo, but because she stuck to a hard no, he sent shepherds to track her down. The shepherds dismembered her, and in so doing transformed her into a virtual, ever-present voice that carpets the Earth.

Many people take myths personally, as if Echo served as their placeholder, an egoic stand-in, and conclude: “Ew, losing a bod sounds grim, and I def don’t wanna be dismembered.” Which is fair enough, but so simple a read that I won’t dwell on it here. And likewise, many commentators have cast Echo in a negative light, focusing far more on the bro-gods with whom she was linked, Pan and and the infamous Narcissus. But if we step back, and regard the tale from an expanded perspective, it gets much more interesting: Echo made a leap that neither Pan nor Narcissus were capable of following—the leap into a purely reflective consciousness.

An echo is a reflection of sound waves.

A mirror is a wave reflector. We typically expect mirrors to reflect light, but depending on their construction, they can just as well reflect sound or even atomic-scale matter.

The most intriguing unpacking of the myth of Echo and Pan I’ve found occurs in the collected works of the depth psychologist Dr. Wolfgang Giegerich.3 It would take another entire essay to fully grapple with his views, so I’ll focus here only on this one aspect of Echo’s metamorphosis: Her firm no and get-the-hell-outta-there response to Pan’s lechery propels her, Giegerich writes, not to a merely safe 3D place, but instead into a “radical, unimaginable leap out of the realm of spatial extendedness altogether into non-space.” And poor Pan, still stuck on a semi-animalistic level, lumbering around Arcadia with his hairy goat legs and crudely-expressed desire, couldn’t possibly follow, or even comprehend her. Such a Pan-consciousness, Giegerich continues, “cannot, or refuses to, transcend itself, and thus… is incapable of following [Echo] the nymph… to the level of ‘echo.’”

In other words, within this narrative, Echo accomplishes a kind of self-transcendence in which she’s distilled, evaporated and sublimated from fleshy nymph into the form of consciousness itself. Echo’s advance, writes Giegerich, is the end of myth, as seen from within a myth. It’s a move from content to form, from semantics to syntax—an irreversible increase in consciousness that foreshadows the ever-more-reflective evolution of not just philosophy, but our consciousness at large, and even further the immense abstraction of our time.

A dear family friend came to the closing event for the show, and asked me, what inspires you? It’s the other way around, I said. Art-making is like a detective hunt for resonance. I get a gut sense that things relate, though I usually don’t understand why. Every day I look at art and writing I admire and Rorschach my ideas further into being, following a bloodhound nose as I fumble my way forward. And out of my failed experiments, something new begins to take shape, ever so gradually coming into focus with a coherence and integrity I could never have planned. I have zero inkling of it when I begin, but when I reflect, there’s always a network of secret, latent threads that make it seem inevitable.

A decade ago I read a collection of essays by W. G. Sebald,4 and after I finished it, I copied out a handful of quotes that held a special resonance for me. Ever since, I’ve been haunted by one in particular, where Sebald writes: I have slowly learned to grasp how everything is connected across space and time.

I think of my dream on a spring night in Winchester, and the stroke my grandma survived 4,000 miles away that evening in Salinas. I think of the dimples and sketchy lines left by a simple fiber net pressed into fresh clay 23,000 years ago, and the utterly abstract, sycophantic neural nets competing for our minds today; of waves as light as silk rippling through Nebraska corn and the WAVES that brought my grandparents together; of little girls across rural Europe “cramped in soul, destroyed in body“5 with hands that danced like spiders as they dressed Kings, Queens and Popes, whose names we’ll never know; of hands that punish and hands that hold. I think of painting with fog and misty tints outside my studio at dawn, as if I could smudge the sky itself onto canvas; of the hundreds of vector files that became thousands of cuts, and chains that pulse in waves. I think of lace and its capacity to conceal as well as reveal, and how one never knows whether it is the web or its emptiness that creates the pattern. I find myself again, scattered in the mirror image of these reflections, somehow both the weaver and the woven. Every echo is a kind of coming home. I think of the moment we sat together on the couch, and everything we couldn’t say. And I think of how 21 years later she returned to ask, would you make a net for me? And with this sculpture, these paintings and words to you, I have.

With thanks to Ewa Słapa, Brad Howe, and Phase Gallery for their generosity in making this exhibition possible, and to Simon for encouraging me to expand the original exhibition text into an essay. All horizontal images are by Evan Mark Walsh.

Nets Through Time by Jacqueline Davidson

Old Handmade Lace by Mrs F. Nevill Jackson

Collected English Papers Volume V and VI by Dr Wolfgang Giegerich

A Place in the Country by W. G. Sebald

beautiful-creative alchemy

It will be difficult for me to describe, without dramatic flattery, how much your process influences me. The way you move through the world awaiting pings from the living network. The book I am writing deals in lace and networks as well, but through mycelia and ESP. I love, also, that when you're visited by ghosts, you don't flinch. Sometimes I think of my father's body rotting into the ground on a small hill where I grew up, and how those nerves in the dirt are finding me now. I hear him much more clearly now that he's not in his body.